Bypassing the Key Attestation API with Remote Devices

If you are a frequent reader or a Guardsquare customer, you probably have realized by now the difficulty of detecting in deterministic ways when a device has potentially gone rogue. These can include when a user manipulates a device with the goal of gaining additional privileges by modifying the operating system’s or the app’s runtime (although this doesn’t always imply a bad intent), or when a piece of malware infects the device with goals like accessing user and app data through exploits and rootkits. Many times, heuristics are used as a way to gain knowledge as to how “compromised” the application’s runtime environment is, but major mobile operating systems also offer ways that allow apps to “attest” whether a device can be considered secure in a more deterministic way. In the case of Android, this can be achieved through the Key Attestation API.

Guardsquare recently observed a novel attack technique against the Key Attestation API, called Remote Key Attestation. The attack consists of delegating attestation requests to a remote device in the cloud, which allows spoofing the data that is validated in order to determine whether the requesting device’s boot chain has been compromised or not.

In today’s post, we will be discussing the security state of the Key Attestation API, including ways that advanced users and attackers have tried to bypass it, the ideas behind Remote Key Attestation, how this fundamentally differs from previous attacks, as well as how to stay alert about hardware-backed Key Attestation API abuse through monitoring server-side components.

The current threat landscape: A cat and mouse game for leaked attestation keys

So far, the most common way with which advanced users and attackers bypassed the Key Attestation API was through the use of what’s commonly known as keyboxes. The premise is simple: the anchor upon which the Key Attestation API works is a set of private keys that is present only in the device’s Trusted Execution Environment (TEE) or Secure Element (SE). These keys are used along their associated certificates, part of a certificate chain of which the root CA is one of Google’s root certificates, and are used to generate the Key Attestation responses. Getting access to a device’s set of private keys is what makes it possible to craft custom attestation responses that mimic those of the device’s TEE or SE.

A keybox is nothing more than an XML formatted file that contains a device’s keys, along with the associated certificate chain. In Google-certified devices, the certificate chain leads up to one of Google’s root CA certificates.

Standard Key Attestation flow

Standard Key Attestation flow

Of course, it’s not possible to simply “use” or “import” these keyboxes in a device without further modifications. Additional software that intercepts the Key Attestation API calls before they reach the TEE is needed to be installed onto the device. Some common examples of this kind of software are TrickyStore and TEESimulator – two of the most commonly used Magisk modules for this purpose.

While root modules like these can leave potential detection vectors, it’s also possible to include similar changes into a modified version of the Android OS. This wouldn’t require the use of root management software or its modules, making a much stealthier setup.

How attackers get access to these keys

The problem with this approach is that it is not easy to get a hold of these keys in order to reconstruct a keybox, since the original key material is securely provisioned at the factory into the device’s hardware and is never exposed or loaded in the memory of the Android OS. So how is it that we are seeing them being shared online?

These are two of the most common ways in which attestation keys are leaked:

- In some cases, the OEMs themselves are the ones who leak them(knowingly or unknowingly). An example of this is when an OEM publishes the decryption keys necessary to extract a keybox found within the firmware upgrade package for one of their devices, along with the tools necessary to flash the device and provision those keys.

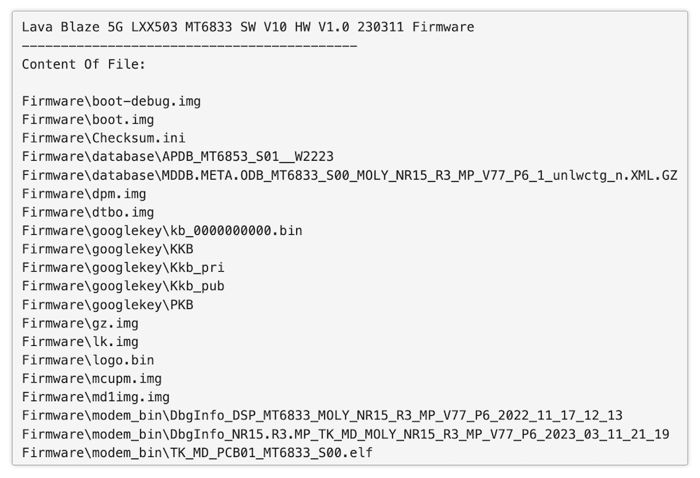

Example of a firmware image containing a Key Attestation keybox; notice the files inside the “googlekey” folder.

- Another method would be to employ a more specialized technique, such as finding vulnerabilities in a device’s TEEs. This allows advanced attackers to either manipulate the way the TEE reports the device’s secure boot state back to the Android OS during Key Attestation, or ultimately to leak the device’s private keys.

In the end, there are many ways with which these keys could be leaked, and these are just some examples of ways in which they could end up in the hands of malicious actors. Because of these leaks, what ends up happening is that these keyboxes get shared slowly but steadily through shady Magisk modules, forums, social network channels or groups, and the locations and formats which with they are shared change rapidly in order to try and extend the keybox’s lifetime before it is inevitably revoked.

Once found publicly on the internet, the leaked key’s serial numbers may end up added in each vendor’s certificate revocation list (CRL), eventually making it to Android’s own CRL, restarting the cycle where a different, unrevoked keybox is used by attackers in order to bypass the Key Attestation API.

The threat evolves: How Remote Key Attestation works

As we have already covered, attackers and users have, so far, found ways to abuse leaked keyboxes in order to craft spoofed Key Attestation API responses. But exposing the keyboxes themselves makes it easy to extract and add their associated certificate serial numbers to a CRL.

For this reason, some advanced Android developers from rooting communities started developing modules which, instead of requiring a keybox to be loaded onto it to craft a Key Attestation response (on-device), the modules relay the Key Attestation request through the network to a remote device. This attack, called Remote Key Attestation (RKA), is being used in order to hide the keyboxes’ private key material from other advanced users, attackers, and vendors who maintain a Key Attestation CRL.

Relay attacks like RKA can be applied in a few different ways. We will be covering a few examples of how they can be set up to either hide the keybox used to generate an attestation response, or to take advantage of device-specific vulnerabilities that allow generation of legitimate-looking Key Attestation responses in order to abuse them from other devices.

Relaying spoofed Key Attestation responses without revealing the Key Attestation keys

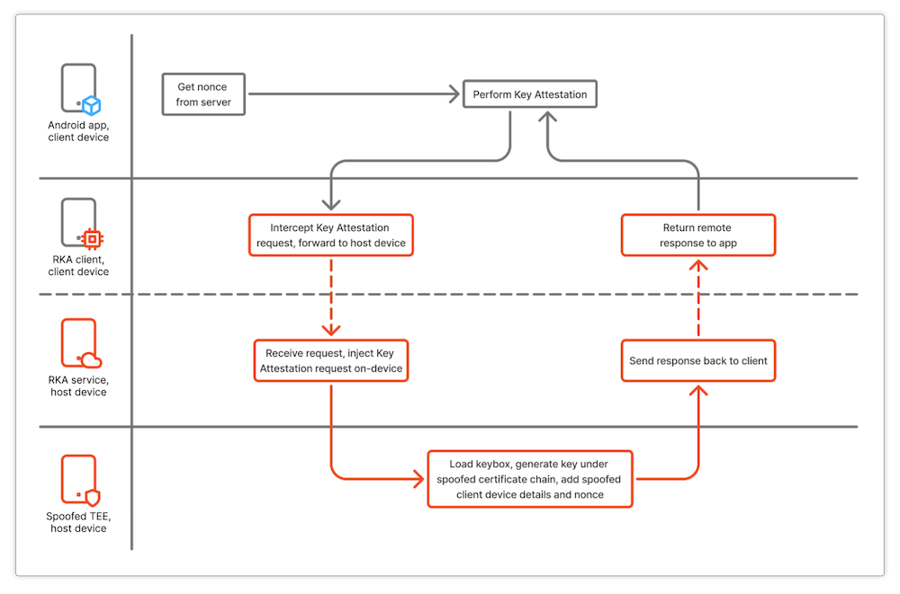

The way this setup works is similar to other Key Attestation spoof related modules, like TrickyStore or TEESimulator. When the Key Attestation API is called, the request is intercepted at the same level as those modules, and a few additional details are collected at the requesting (“client”) side, including the nonce and all the necessary details that identify the requesting app. The collected data is transmitted to the remote device (“host”), which is an Android device that has been bootloader unlocked, and where a program is listening for incoming network requests. This program has elevated privileges within the host device, and as such it can perform a Key Attestation request whilst replacing the necessary request details (nonce, app details) at the same level as they were captured on the client device. In turn, the Key Attestation API is called on the host device, and using the keybox loaded in the device, it will generate a spoofed Key Attestation response with the details from the client device and app.

RKA flow using legacy “fused” keyboxes

Using this scheme, advanced users and attackers can abuse a keybox located in a given host device throughout a multitude of client devices, without the keybox ever being exposed directly on the internet.

Relaying legitimate Key Attestation responses from vulnerable devices

As an alternative, groups or individuals could also abuse a device vulnerable to a boot chain exploit by setting it up as a RKA host device. The idea is that if they are able to exploit the device to make it believe it’s bootloader locked, while in reality it’s running a modified boot image with root management software, they can then relay Key Attestation responses from this device to others which would otherwise not be affected by the exploited vulnerability. This is an example of how attacks like RKA not only allow hiding of key material and spoofing traces, but also relay a legitimate device’s TEE and SE responses as well.

One such boot chain exploit that allows spoofing of the device’s bootloader lock status is kaeru, a custom Mediatek boot chain payload that allows executing arbitrary code and modifying the behavior of the device’s Little Kernel (LK) on supported models.

Remote Key Attestation flow using a real TEE/SE following a boot chain exploit

Remote Key Attestation flow using a real TEE/SE following a boot chain exploit

Thanks to a setup like this, users are able to modify their bootloader to report to both Android and TEE/SE that the device is bootloader locked, while allowing them to install root management solutions onto the device.

Android platform countermeasures against Key Attestation attacks

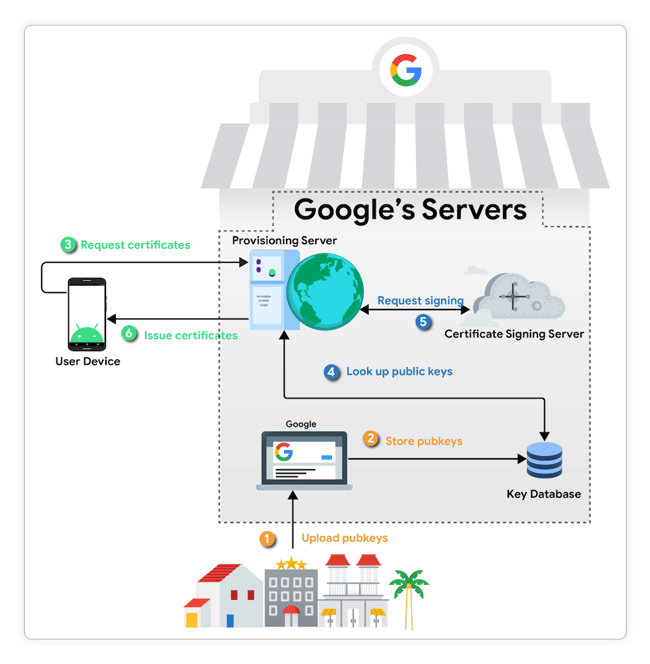

A recent development in the Android ecosystem aims to put a stop to the underlying problem behind Key Attestation attacks through the use of remotely provisioned keys with a protocol known as Remote Key Provisioning (RKP).

Remote Key Attestation flow using a real TEE/SE following a boot chain exploit

In contrast with keyboxes, RKP allows retrieval of recurring, short-lived key material from a remote provisioning partner after authenticating the device, using a device-generated secret of which its public key got extracted at the factory rather than embedding (“fusing”) long-lived key material at the factory. Thanks to RKP, the concept of keyboxes is no longer relevant, since nobody except the device has access to the private key material, and thus an advanced attack against the device’s secure hardware is required in order to lift any of its secrets.

Notably, the adoption and switch from fused keyboxes onto RKP is still ongoing at the time of publication, making it difficult to prevent the abuse of the Key Attestation API until a full transition from one scheme to the other happens and legacy fused devices stop being trusted for Key Attestation purposes at all.

The impact of switching to RKP for relay attacks like RKA

In short, relay attacks remain effective but with a much limited scope. From the two kinds of setups we described, only the ones where a boot chain vulnerability is exploited would still be able to work under RKP. This is because in RKP there are no long-lived secrets and an attack against a device’s TEE or SE would expose the short-lived key material provisioned at runtime. Because of this, specialized setups that exploit device vulnerabilities are required. As an example, the boot chain exploit previously mentioned (kaeru) supports several devices which are provisioned using RKP.

For this reason, even when using the latest platform attack countermeasures, it’s important for applications to perform active monitoring of collected device signals in order to understand whether Key Attestation responses are being relayed or reused across different devices.

Backend-first monitoring strategies against Key Attestation attacks

Novel attack techniques like RKA push app developers to stay vigilant and collect as much environmental data as needed in order to determine whether a given attestation request can be trusted or not.

We have just seen the evolution of attacks against the Key Attestation API, and how blindly trusting its response isn’t enough to ensure in a deterministic way that the response hasn’t been crafted and that the device can be considered secure. To prevent abuse, the Key Attestation API response can be complemented with active monitoring from an application’s backend, as well as varied detection and prevention strategies.

Here are a few examples of how this can be achieved:

- Collecting environment data helps correlate and understand whether a given Key Attestation response really belongs to a legitimate device’s TEE or SE. With the surge of attacks like spoofed responses through keyboxes and RKA, this is becoming more and more important.

For example, a legacy “fused” key0x1a2b3c4dbelonging to a device from OEM A should not be reported being used by a device from OEM B or OEM C. Similarly, it should not be the case that a remotely provisioned key is seen shared across notably different devices, since these keys are expedited per each device.

On top of these, fingerprinting other device characteristics and usage patterns – associated with the collected Key Attestation data – helps aggregate the usage of Key Attestation keys across different distinct devices and facilitate spotting cases of abuse. - After collecting the necessary environment data, set up automated detection and action rules. Relay attacks like RKA offer a very fast response time to key revocations due to their client-host nature, where the host device can be changed or its key material replaced, depending on the setup used.

For this reason, having automations that allow real-time abuse detection is very important. In this case, relying on collected data and seeing how it fluctuates through time (e.g., noticing specific key usage spikes or changes in the device’s environment variables) can help in setting up automated backend action rules to prevent abuse.

Response actions could include revoking specific keys or considering specific devices less secure or treating them differently, depending on your business’ threat model. This switches the detection-and-action paradigm from the slow-paced CRL approach to a more dynamic, observation-based rule system. - Use a multi-layered approach, like the one Guardsquare offers. When a device has already been modified and an application is being targeted, it is likely that just having an unlocked bootloader to gain ‘root’ privileges is not the only vector being used for an attack, and that a device being bootloader unlocked or rooted does not necessarily imply bad intent from the user. In fact, depending on the application’s implementation, just having root doesn’t suffice for achieving an attacker’s goals of a certain complexity against an application. (Examples of how attackers approach applications with malicious goals can be seen in our blog post “I Just Bypassed Your App’s Payment Process”.)

- Lastly, app attestation allows applications to cover beyond what the Key Attestation API offers and ensure that the application interacting with a given backend is legitimate and can be trusted in order to prevent API abuse. On top of that, app attestation allows policy changes and can react to attacks from the server-side without needing to change the application’s code in many cases, making it as fast paced and reactive as the novel attacks covered throughout today’s post.